‘The archaeological excavator’ wrote Mortimer Wheeler, ‘is not digging up things, he is digging up people.’ But what happens when we go so far back into our evolutionary past that things rarely survive? And how do we conceive of the animals/people who made those things when they have no biological parallel in the modern world?

‘The Artificial Ape’, a new book written by Timothy Taylor, tackles this question, coming to the startling conclusion that rather than humans evolving to create technology, technology evolved to create humans.

Things, literally, came before people…

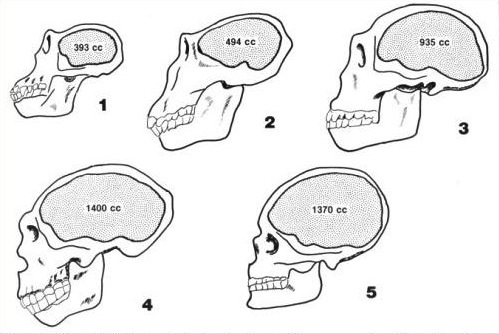

Beginning with the observation that humans are the weakest of the seven species of ape on the planet, Taylor asks the simple question – how did we manage to come out on top? An assessment of modern day primates shows that we somehow evolved from A to C, losing our biological advantages whilst quadrupling brain size. What’s not clear is how we got through the B steps, or what the selective pressures were for a smart but weaker ape to arise.

Beginning with the observation that humans are the weakest of the seven species of ape on the planet, Taylor asks the simple question – how did we manage to come out on top? An assessment of modern day primates shows that we somehow evolved from A to C, losing our biological advantages whilst quadrupling brain size. What’s not clear is how we got through the B steps, or what the selective pressures were for a smart but weaker ape to arise.

The evolution of intelligence is usually explained as the consequence of an increasingly involved and demanding social life, leading to the development of larger brains. By applying our newfound cranial capacity to the invention of tool use, we were eventually granted mastery over the natural world. But this actually ‘leap frogs’ the B steps, and leads to what Taylor calls the ‘smart biped paradox.’

Upright walking places significant mechanical constraints on the pelvis. It narrows the birth canal, and should have ruled out any subsequent cranial expansion; and as expected, for the first three million years of upright walking brain size remained relatively unchanged. But then the genus Homo emerged, and over the space of half a million years, brain size doubled, tripled and quadrupled into the modern range. The secret, argues Taylor, is in the timing.

“This book insists that there was an actual moment when we became human. It was a moment long before we became intelligent in any modern sense. It was a moment seized by a female as, for the very first time, she turned to technology to protect her child. In that moment, everything that we were going to become was made not just possible, but inevitable.” Page 2.

Darwin’s solution was based on sexual selection. Our early female ancestors would have a natural inclination to smarter, large headed males, with male and female offspring benefiting from this choice through an evolutionary increase in brain size. But the trouble with this model is that it doesn’t match the evidence – there is a gap of 192,000 years between the occurrence of the first stone tools in the archaeological record and the emergence of the first species of the larger brained genus homo. Taylor’s argument is that it was our engagement with technology, particularly the baby sling, which allowed us to assume control of our evolution. With the baby sling we became a ‘marsupial ape,’ able to continue our gestation outside the womb.

Darwin’s solution was based on sexual selection. Our early female ancestors would have a natural inclination to smarter, large headed males, with male and female offspring benefiting from this choice through an evolutionary increase in brain size. But the trouble with this model is that it doesn’t match the evidence – there is a gap of 192,000 years between the occurrence of the first stone tools in the archaeological record and the emergence of the first species of the larger brained genus homo. Taylor’s argument is that it was our engagement with technology, particularly the baby sling, which allowed us to assume control of our evolution. With the baby sling we became a ‘marsupial ape,’ able to continue our gestation outside the womb.

Our brains were imprinted with an increasingly complex culture – ‘the substrate for the development of language and symbolic culture, which essentially hard-wires itself into our biology ex utero.’ This changed the ‘algebra of the biologically possible,’ undermining the process of natural selection and the survival of the fittest. Taylor extends his analysis into the present day, arguing that biologically we are getting weaker still – but by pushing the frontiers of scientific technology into a cybernetic realm of prosthetics, intelligent implants and artificially modified genes, this no longer matters. We are an ‘Artificial Ape,’ evolved by technology that is itself driven by its own unfolding logic.

Our brains were imprinted with an increasingly complex culture – ‘the substrate for the development of language and symbolic culture, which essentially hard-wires itself into our biology ex utero.’ This changed the ‘algebra of the biologically possible,’ undermining the process of natural selection and the survival of the fittest. Taylor extends his analysis into the present day, arguing that biologically we are getting weaker still – but by pushing the frontiers of scientific technology into a cybernetic realm of prosthetics, intelligent implants and artificially modified genes, this no longer matters. We are an ‘Artificial Ape,’ evolved by technology that is itself driven by its own unfolding logic.

The Artificial Ape

This book is excellently written, meticulously researched and provocatively pitched. It floats like a butterfly; it stings like a bee. Whilst some readers (of a certain theoretical persuasion) will be driven to distraction by Taylor’s argument, they better bring their ‘A’ game if they want to take him down.

Timothy Taylor is a Yorkshire Dales cave archaeologist, Reader in archaeology at Bradford University and Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of World Prehistory, and he has written two other popular anthropology books – The Prehistory of Sex: Four Million Years of Human Sexual Culture, and The Buried Soul: How Humans Invented Death. As a regular contributor to popular science TV programmes and websites, his success rests on the ability to explain complex thought with artful simplicity – a skill that appears to be woefully lacking in the archaeological profession.

Timothy Taylor is a Yorkshire Dales cave archaeologist, Reader in archaeology at Bradford University and Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of World Prehistory, and he has written two other popular anthropology books – The Prehistory of Sex: Four Million Years of Human Sexual Culture, and The Buried Soul: How Humans Invented Death. As a regular contributor to popular science TV programmes and websites, his success rests on the ability to explain complex thought with artful simplicity – a skill that appears to be woefully lacking in the archaeological profession.

Why, we might ask, has there never been a prize-winning popular archaeologist writer? Why has an archaeologist never won the Pulitzer Prize, or a ‘science booker’ – no Richard Dawkins, no Jared Diamond’s? Contrary to Mortimer Wheeler’s advice, it seems we are content to go on letting archaeologists dig up things not people. For every Staffordshire Hoard that captures the public’s attention, there are a thousand self-satisfied archaeologists happy to turn out yet another book peering into the minutiae of their own subject. Big answers to little questions.

By asking what makes us human, and reflecting on what that might mean for our future, this book bucks the trend.

Watch Taylor lecture on The Artificial Ape here…

And buy it here…

“Big answers to little questions”

Painfully true.

Great review. I’m interested in reading his books now. I found you through 4 Stone Hearth.

Great stuff Brian. ‘The Buried Soul’ is a classic, and ‘The Prehistory of Sex’ remains the only book that both archaeologists and non-archaeologists see on my bookshelves and make an instant bee-line for.

It’s archaeology, but not as wee know it!