If archaeology be the food of love, then dig on!

Here’s a handful of tunes playing on our on site iPod at the moment.

What’s playing on yours??? Read more

If archaeology be the food of love, then dig on!

Here’s a handful of tunes playing on our on site iPod at the moment.

What’s playing on yours??? Read more

Love this photo – taken by someone who (worringly it has to be said) calls themselves ‘Shovelbumming.’ Read more

More than 150 years after a 24-year-old Scottish Egyptologist, shipped back what has come to be known as the ‘Rhind Mummy,’ Read more

For anyone who has ever felt even the slightest bit claustrophobic in a small room or lift, the thought of cave diving – exploring dark submerged tunnels hundreds of feet underground with only a limited air supply – is excruciatingly uncomfortable.

To tick a difficult cave system off the list is meat and drink to the hardy cave-diving folk, who experience real joy in exploring underground backwaters and blind alleys in vast networks of twisting underground shafts, in the hope that they may discover new connections and caves systems.

Headlines were made last year when cavers digging through deep tunnels 100 metres below ground came close to linking separate cave systems in Lancashire, Yorkshire and Cumbria (Daily Mail 17th January 2011). Fossil cave systems become silted with mud and rocks, and cavers toiling to open these passageways occasionally come into contact with archaeological material. As the work to open up a passageway in Lancashire at Leck Fell demonstrates, the caving community are every bit as good as the archaeologists when it comes to recording archaeology underground – and perhaps a lot more nimble.

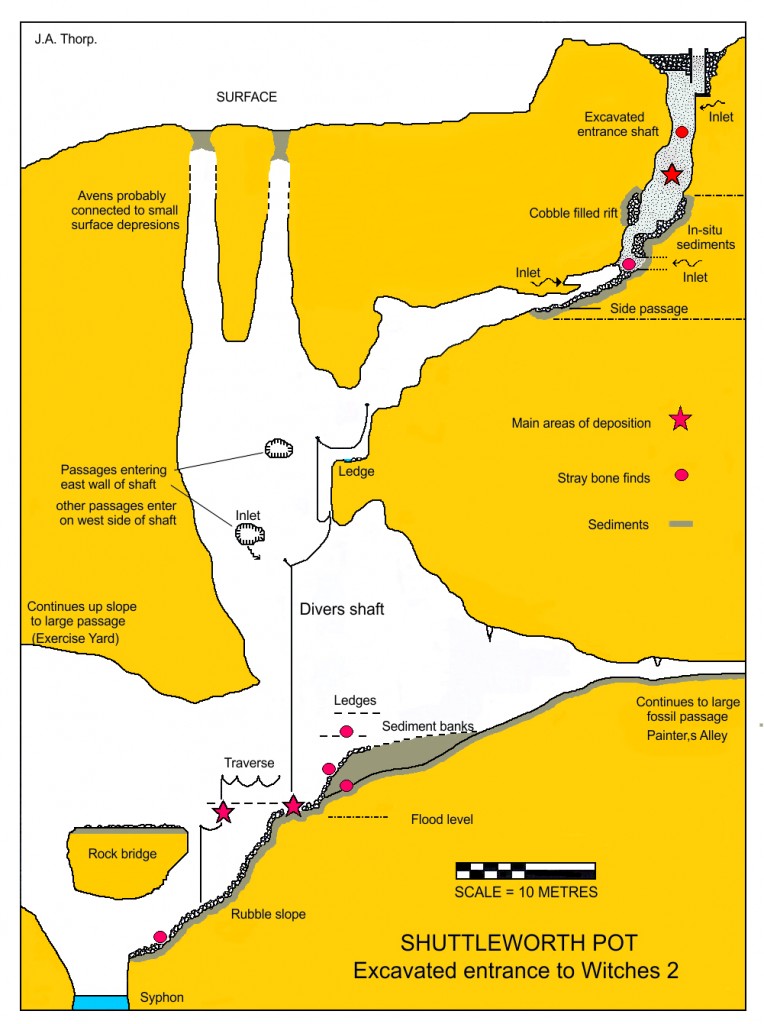

The story of Shuttleworth Pot began in 1997, when cave divers Jason Mallinso and Rick Stanton made an epic 1160 metre cave dive. Pock-marked with sinkholes and a near absence of surface drainage, a network of subterranean caves twist below Leck Fell, and the cavers were trying to connect two of them: ‘witches’ and ‘Pippkin.’ Part way through the dive they surfaced into a large chamber, which they called ‘House of the Rising Sump.’ Before continuing, they noted dry passageways leading off towards the surface, but no sign of light. If a surface entrance could be found, the chamber would make an excellent staging post for later expeditions. Ten years later, with permission from Andrew Hinde at Natural England and the landowner to excavate a sinkhole, a team of cavers from the Council for Northern Caving Clubs put plans into action, and the exploration of Shuttleworth Pot began.

Shuttleworth Pot

The first job for the cavers was to ensure that they were digging in the right place. They placed a radio beacon in the cavern as close to the surface as they could. Readings from above on Leck Fell detected a signal coming from a sinkhole, suggesting the beacon was between 5-17 metres below ground.

A small dig showed that the top layers were composed of a relatively recent infilling of peat, followed by cobbles and alluvial deposits that had been formed from the sides of the sinkhole, which had collapsed inwards when it was fed by an active stream.

The shaft was excavated downwards for 8 metres, before it veered off to a depth of 16 metres, entering the cavernous space discovered by the cave divers. Animal bones were collected, overseen by experienced caver and amateur archaeologist John Thorp, and identified by Tom Lord. The bones were found to cluster in two distinct concentrations: location 1 (directly below the cave entrance) and 2 (deep within the cave on a small flat section of cobbles). The location 2 assemblage included goat, horse, pig and sheep, and had probably been washed into the cave from an adjacent passage, accumulating on the cobbles above the high water mark. Two small and delicate palmate newts were also identified from deep within the cave – the first recorded examples from cave environments.

The location 1 bones included a number of domestic and wild species: human, dog, domestic pig, domestic cattle (with a flint tool cut mark), sheep or goat, wolf, red deer, black grouse and wild cattle (aurochs). With no radiocarbon dating evidence it is difficult to properly interpret this assemblage, but theses are perhaps more informative to the human picture than the bones discovered deeper in the cave. The mix of wild and domestic species is similar to that found at a similar cave 4 km away – North End Pot – were bones were found at a similar depth below ground were dated to 2700 BC. With large predators such as wolf and wild boar roaming the landscape, herdsmen would have been on constant vigil.

Prior to the formation of blanket peat in the Bronze Age, Leck Fell would have been a very different landscape, with small clearings interspersed with areas of dense scrub woodland. Sinkholes would have been much deeper, and posed a constant hazard to domestic animals and wild animals, with scavengers succumbing to the same fate. Exploring one of the side passages, the cavers found one of the most poignant finds. In a shallow scoop in the cave floor, a medium sized dog skeleton was curled up, as though it had lay down and died. The dog would not have survived falling down the entrance from Shuttleworth Pot, so it must have come in from an unknown entrance, only to become lost in the dark. It does put one in mind of the much luckier terrier that discovered Victoria Cave, but lived to point the way.

Amateurs

The Shuttleworth Pot excavation stands proud alongside the hi-tech professional laser survey of the subterranean Nottingham city caves reported in CA 260. The Shuttleworth Pot artefacts and site survey has been published, and a selection of bones will be dated with funds provided by Natural England and the British Cave Research Organisation. This was an amateur excavation in the truest sense. Following the Latin amare – meaning to love – cavers are clearly passionate about their sport, but through initiatives like the Upland Cave Network have also become adept amateur archaeologists. With sharp eyes trained on new cave discoveries, we can only hope that cavers get there before the badgers.

***

‘Shuttleworth Pot into Witches Cave II’ can be found through the Council for Northern Caving Clubs [see HERE] Many thanks to John Thorpe, Pete Monk, Tim Taylor, Hannah O’Regan, John Howard and Tom Lord for sharing their photos, words, experience and insights. Looking forward to hearing more soon!

Download the full article here…